In addition to our regular course evaluations, which we'll dispense with on Wednesday, the English Department is conducting a brief survey of students as part of our ongoing efforts to anticipate and meet the needs of our students. Please take a few minutes to respond to the questions, which you'll find here. You'll also need our class code, which is F1099, and take note that this course fits under the LCS heading.

Sunday, November 27, 2016

Sunday, November 20, 2016

Updated Schedule and Skype URL

Thanks again to everyone for your understanding regarding the changes we've had to make to our schedule this semester. Here's an updated breakdown of our final classes:

- Mon. November 21: Skype video chat on conclusion of Deadeye Dick

- Weds. November 23: No Class — Pre-Thanksgiving

- Fri. November 25: No Class — Thanksgiving

- Mon. November 28: Galápagos book 1, ch. 1–25 (respondents originally scheduled for 11/18 and 21 will present)

- Weds. November 30: Galápagos book 1, ch 26–book 2, ch. 2 (respondents originally scheduled for 11/28 will present)

- Fri. December 2: Galápagos book 2, ch 3–14 (respondents originally scheduled for 11/30 will present)

Monday's video chat is optional — I understand everyone might not be able to make it to a computer at that time or be familiar with Skype — but at the very least I wanted to present an opportunity for everyone to talk about the end of Deadeye Dick and for those scheduled to present to share their thoughts. It might be helpful to gather several people together around one laptop. At any rate we'll play it by ear.

We'll keep the same time-slot as our regular class, though I'll pop in a few minutes early. Here's the Skype URL for the group chat I've set up: https://join.skype.com/wLZZEwt9NnZS.

Friday, November 4, 2016

Your Final Projects

Like all good things, our semester with Vonnegut will soon come to an end, but not unlike the "cleaning-up" that Billy Pilgrim and his fellow POWs find themselves doing in Dresden as World War II wraps up, we (well, you) have a little more grim and dirty work ahead of you.

It's a final essay, but it's not . . .

In a literature class like this, one would expect to be asked to write a scholarly essay making some sort of critical argument that's supported by (con)textual evidence from the quarter's readings (all of which is properly cited in MLA format). Vonnegut's work, however, doesn't necessarily call for the same response as other authors and so instead of a straightforward essay, I'd like you to produce a creative piece that — for all intents and purposes — achieves all of those same goals.

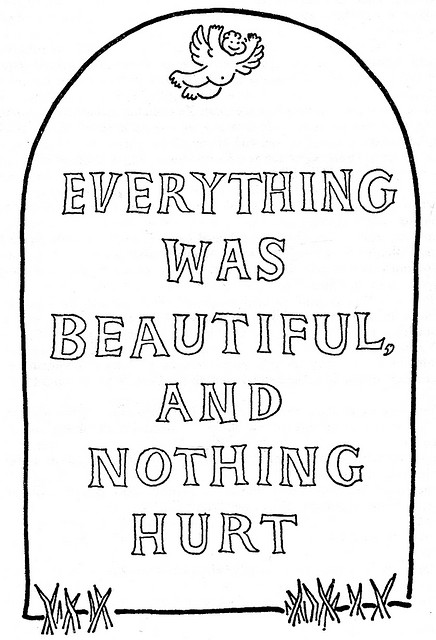

Let's leave form aside for a second and focus on function instead. Vonnegut's been dead for nearly a decade now, though he was as fiery a social commentator in his final years as he'd ever been . . . even more fierce, perhaps. What I'd like you to do in your final project is to pick up his gauntlet and carry on in his stead. Choose a contemporary issue that's important to you and write a creative piece that aims to capture your best estimation of what Vonnegut's stance on the topic would have been, in his style, and using anecdotes, examples, characters, etc. from the nine novels you've read this quarter as evidence to support that position. You could easily have a field day with election year politics, or choose a very recent topic like Black Lives Matter, the refugee crisis, gay marriage, reproductive rights, or work in a more general direction addressing perennial favorites like civil rights, censorship, the military-industrial complex, etc. Find something that gets you riled up and channel Vonnegut's perspective to analyze and propose solutions to the issue at hand.

How about some examples?

So how do you get the creative and the critical components working together? First, pay attention to some of the hybrid writing the Vonnegut's doing in the latter years of his life. The epilogue to Jailbird is an excellent model for your work, as are Vonnegut's bookend chapters (nos. 1 and 10) of Slaughterhouse-Five, Jonah's more meta-narrational moments in Cat's Cradle, the preface to Deadeye Dick, and Vonnegut's own presence in Breakfast of Champions. A part fiction/part nonfiction approach will serve you well. Remember that you don't need to tell a fully-formed story with a beginning, middle and end — think of it more in the mode of occasional storytelling, as if you happened to sit down next to a stranger at a bar and struck up a conversation, and don't forget Vonnegut's very helpful writing tip of having one particular person in mind when you're writing (he often wrote to his sister Alice).

The most useful tactic at your disposal, and a very Vonnegut-ian one, is to make extensive use of allegory in your work. Of course, not only is Vonnegut an agnostic humanist who can see the value of faith for others and quote extensively from the bible, but he's also a big believer in one of Christ's favorite literary devices: parable. There's perhaps no better (and more commonly used) example of this in Vonnegut's writing than Kilgore Trout, whose stories serve to make points in a more vivid way than mere explication ever could. Likewise, think of the tangential characters who aren't directly connected to a storyline but serve an important purpose furthering the ideas behind the novels — like Powers Hapgood and Sacco and Vanzetti in Jailbird, or the brief mention of RFK and MLK in Slaughterhouse-Five. Use Vonnegut the way he uses Kilgore Trout, or use Trout the way Vonnegut uses Trout, or use Vonnegut's other characters in the same fashion.

Another approach, particularly if you've never written fiction before. Channel Frank and Newt Hoenikker staging bug battles inside a mason jar: pick a few characters, pick a location to drop them in, and shake the jar a bit. See what happens.

In terms of the argument you're going to make, you'll have to work through precedent — points of view expressed in the works we've read that you feel are applicable to the issue you're addressing. Vonnegut's certainly opinionated and not at all shy about sharing his ideas, so you should have plenty of material to make use of in your piece.

Aside from all of the texts mentioned above, here — to give you a taste of Vonnegut's most pointed writing in a political mode — are a few superlative selections from Vonnegut's last book published during his lifetime, A Man Without a Country (2005), which collected a number of essays he penned for the news magazine, In These Times:

- "State of the Asylum," which includes a dialogue between Vonnegut and Trout

- "Cold Turkey," perhaps the most famous of Vonnegut's ITT pieces

- "Requiem for a Dreamer," the final dialogue between Vonnegut and Trout, who committed suicide soon thereafter (disregard the fact that he died in Breakfast of Champions, or that according to Jailbird he's a pseudonym for Dr. Robert Fender)

- "American Xmas Card 2004"

Anything else I should know?

Here are a few important guidelines for your final projects — fail to meet these requirements and, well, you'll fail(!):

- Length: 6–8 double-spaced pages minimum — that's full pages, and not counting your works cited list, so to be safe, make sure your piece goes on to page 7. Another reasonable minimum would be 2000 words. If the spirit moves you and you find yourself writing a longer piece, please don't feel constrained by the 8 pg. limit (that's just a general ballpark length to aim for). On the other hand, if you hand in a paper that's less than 6 full pages, you'll automatically receive an F (so don't do that).

- Formatting — particularly since you're sending your file to me electronically, it would not be wise to play around with margins, get cutesy with font sizes, etc. 12 point Times New Roman is lovely and easy on the eyes, to boot. Barring that, Cambria or a similar serif typeface (serifs, don't ya know, are those little decorative doohickeys at the ends of the letter) will be fine. I'm partial to the restrained elegance Goudy Old Style (but that's just me).

- MLA citations and works cited list — you'll find links to MLA resources here. Don't forget that you need to cite paraphrases and summaries of source texts in addition to direct quotations. This is not easy to do for an assignment like this, but give it your best shot and it'll be fine.

- No block quotes — there is, perhaps, no greater comfort to the unprepared last-minute writer than the block quote — just cram it all in there, making no attempt to trim the text (or disguise the fact that you're cutting and pasting from Wikipedia). In formal essays of lengths longer than what you're being asked to deliver here, I might allow students to use one block quote in their essay, but there's no reason whatsoever for block quotes in a final project like this. Trim quotes to their essentials and/or interweave them throughout your sentences.

- Due date — Tuesday, December 6th at 6:00PM. Please send your final to me at my gmail address (which is my last name [dot] my full first name at gmail.com) as an attachment. When I get your paper, I'll download it to make sure that it opens without issue and then write you a little note confirming that I've received it. Don't forget that late assignments will be docked accordingly. The absolute latest I can accept a paper is Saturday, December 10th.

Wednesday, November 2, 2016

Weeks 13–15: Galápagos

Over the course of our last few readings, we've seen a very different Vonnegut — one who's coming to terms with both the process of aging and his own shifting role in American arts and letters, and responding in kind with a strong pair of novels (Jailbird and Deadeye Dick) that are humanistic, character-driven affairs that stay largely within the realm of conventional (though still wild) reality. This pattern will continue in Bluebeard, the third of four books marking a late high-point in Vonnegut's career (sandwiched between two of his worst offerings: Slapstick and Hocus Pocus), however, in Galápagos, the author is more than happy to cast off the fetters of everyday existence and explore a fantastic, science-fiction future.

Nonetheless, Galápagos is very much a novel of its time: the worldwide financial woes that set the stage for the book's narrative speak to real-life stagnation in the early and mid-80s and it's no stretch to read the bacterial disease that makes all women but those on Santa Rosalia infertile as Vonnegut's attempt to address the AIDS crisis. The Galápagos islands, likewise, serve not only as a setting for the novel but as a symbolic tie to Charles Darwin, who formulated his theory of evolution after investigating the novel ways in which the species native to the islands had developed in isolation. In Jailbird, Vonnegut ruminates on the nature of the island and its occupants while describing scene at the Hotel Royalton's Coffee Shop on Walter's fateful first full day of freedom in NYC:

Nonetheless, Galápagos is very much a novel of its time: the worldwide financial woes that set the stage for the book's narrative speak to real-life stagnation in the early and mid-80s and it's no stretch to read the bacterial disease that makes all women but those on Santa Rosalia infertile as Vonnegut's attempt to address the AIDS crisis. The Galápagos islands, likewise, serve not only as a setting for the novel but as a symbolic tie to Charles Darwin, who formulated his theory of evolution after investigating the novel ways in which the species native to the islands had developed in isolation. In Jailbird, Vonnegut ruminates on the nature of the island and its occupants while describing scene at the Hotel Royalton's Coffee Shop on Walter's fateful first full day of freedom in NYC:

I thought to myself, "My goodness — these waitresses and cooks are as unjudgmental as the birds and lizards on the Galapagos Islands, off Ecuador." I was able to make the comparison because I had read about those peaceful islands in prison, in a National Geographic loaned to me by the former lieutenant governor of Wyoming. The creatures there had had no enemies, natural or unnatural, for thousands of years. The idea of anybody's wanting to hurt them was inconceivable to them.

So a person coming ashore there could walk right up to an animal and unscrew its head, if he wanted to. The animal would have no plan for such an occasion. And all the other animals would simply stand around and watch, unable to draw any lessons for themselves from what was going on. A person could unscrew the head of every animal on an island if that was his idea of business or fun (123-124 in my first edition hardcover, 174-175 in your paperbacks).

At the same time, while forces beyond human control do their part to shape the novel, it's worth noting that Vonnegut also finds fault within human action and intention — big brains and big ideas cause big problems. While the novel's characters undergo physical transformations as they evolve, their brains change as well, getting smaller, and as far as Vonnegut is concerned (cf. this somewhat bombastic Los Angeles Times article), this is all for the best:

The big trouble, in Kurt Vonnegut's view, is our big brains.

"Our brains are much too large," Vonnegut said. "We are much too busy. Our brains have proved to be terribly destructive."

Big brains, Vonnegut said, invent nuclear weapons. Big brains terrify the planet into worrying about when those weapons will be used. Big brains are restless. Big brains demand constant amusement.

"Our brains are so terrifically oversized, we have to keep inventing things to want, to buy," Vonnegut said with a shudder. "If you think of the 8 million people of greater New York charging out of their houses every day in order to monitor the planet, it is a terrifyingly destructive force. [...]

"Among other things," he said of this giant computer lodged between humanity's collective ears, "it is capable of creating the Third Reich of Germany, which in fact so demoralized the world that I don't think we'll ever recover."

The brain: "I think stupidity may save us," Vonnegut said. "I think we are too damned smart."

Finally, take note that the events of the novel take place in 1986, just one year after its completion, and the proximity is intentional on Vonnegut's part — if we don't wise up, he reasons, such fantastic events are not at all out of the realm of possibilities for the human race.

Here's our reading schedule for Galápagos:

- Fri. November 18: book 1, ch. 1–14

- Mon. November 21: book 1, ch. 15–25

- Weds. November 23: No Class — Pre-Thanksgiving

- Fri. November 25: No Class — Thanksgiving

- Mon. November 28: book 1, ch 26–book 2, ch. 2

- Weds. November 30: book 2, ch 3–14

And here are a few supplemental links:

- "How Humans Got Flippers and Beaks," The New York Times' review of Galápagos: [link]

- "Vonnegut Explores the Big Brain Theory," Los Angeles Times' review of the novel: [link]

- a second LAT review of the book: [link]

- an interview with Hank Nuwer that's largely concerned with Galápagos: [link]

- an NPR essay by Ron Currie, Jr., who names Galápagos one of his "Three Books to Help You Enjoy the Apocalypse": [link]

- "Evolutionary Mythology in the Writings of Kurt Vonnegut Jr.," Gilbert McInnis' 2005 essay, which originally appeared in Critique: Studies in Contemporary Fiction: [link]

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)